Signs and symptoms of MAS

How does MAS present?

MAS can be difficult to diagnose, as signs and symptoms are often nonspecific but can lead to multiorgan failure and death if not treated promptly. These signs and symptoms can also closely resemble those of sepsis or a rheumatic disease flare, which are important to consider in pursuing a differential diagnosis.1

When MAS occurs as a complication of Still’s disease, the rheumatic condition it is most often associated with, it is estimated to occur in up to:

Often times, MAS can manifest as the first sign of underlying Still’s disease, so it’s critical to maintain suspicion of MAS in patients who may be undiagnosed as well as in patients with known disease.4-6

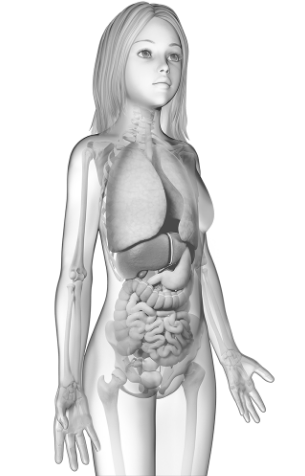

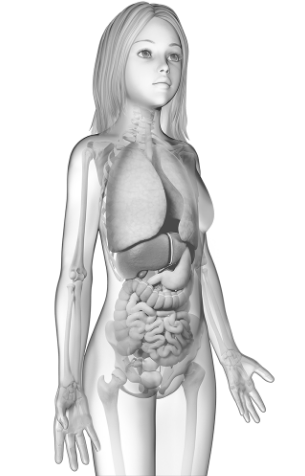

See below for more information about some of the commonly observed signs and symptoms of MAS.

CNS=central nervous system; CRP=C-reactive protein.

Please note that the manifestations of MAS can vary significantly among patients. It is important to monitor all relevant labs and assessments for an individual patient based on their clinical condition. ALT=alanine aminotransferase; AST=aspartate aminotransferase; CXCL9=chemokine (C-X-X motif) ligand 9; LDH=lactate dehydrogenase; sCD25=soluble cluster of differentiation 25.

Subclinical MAS

Subclinical MAS is more difficult to detect due to the absence of fever and/or lower levels of ferritin, CRP, and triglycerides. In these cases, some patients receiving treatment for their rheumatic disease may experience fewer symptoms and have less prominent laboratory changes compared to patients who are not currently on treatment.1,20 It is estimated that up to 40% of children with sJIA may have subclinical MAS.3

Even when lab values are in a normal range, monitoring trends over time can help identify subclinical MAS that may otherwise go undetected.1

References: 1. Lerkvaleekul B, Vilaiyuk S. Macrophage activation syndrome: early diagnosis is key. Open Access Rheumatol. 2018;10:117-128. doi:10.2147/OARRR.S151013 2. Giacomelli R, Ruscitti P, Shoenfeld Y. A comprehensive review on adult onset Still’s disease. J Autoimmun. 2018;93:24-36. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2018.07.018 3. Ravelli A, Minoia F, Davì S, et al. 2016 classification criteria for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation Collaborative Initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(3):566-576. doi:10.1002/art.39332 4. Minoia F, Davì S, Horne A, et al. Clinical features, treatment, and outcome of macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a multinational, multicenter study of 362 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(11):3160-3169. doi:10.1002/art.38802 5. He L, Yao S, Zhang R, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in adults: characteristics, outcomes, and therapeutic effectiveness of etoposide-based regimen. Front Immunol. 2022;13:955523. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.955523 6. Sen ES, Clarke SL, Ramanan AV. Macrophage activation syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2016;83(3):248-253. doi:10.1007/s12098-015-1877-1 7. Monteagudo LA, Boothby A, Gertner E. Continuous intravenous anakinra infusion to calm the cytokine storm in macrophage activation syndrome. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(5):276-282. doi:10.1002/acr2.11135 8. Carter SJ, Tattersall RS, Ramanan AV. Macrophage activation syndrome in adults: recent advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(1):5-17. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key006 9. Price B, Lines J, Lewis D, Holland N. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a fulminant syndrome associated with multiorgan failure and high mortality that frequently masquerades as sepsis and shock. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(6):401-406. doi:10.7196/samj.7810 10. Henderson LA, Cron RQ. Macrophage activation syndrome and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in childhood inflammatory disorders: diagnosis and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2020;22(1):29-44. doi:10.1007/s40272-019-00367-1 11. Avau A, Matthys P. Therapeutic potential of interferon-γ and its antagonists in autoinflammation: lessons from murine models of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and macrophage activation syndrome. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2015;8(4):793-815. doi:10.3390/ph8040793 12. Shakoory B, Geerlinks A, Wilejto M, et al. The 2022 EULAR/ACR points to consider at the early stages of diagnosis and management of suspected haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome (HLH/MAS). Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75(10):1714-1732. doi:10.1002/art.42636 13. Wang R, Li T, Ye S, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome associated with adult-onset Still’s disease: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(8):2379-2386. doi:10.1007/s10067-020-04949-0 14. Bracaglia C, Prencipe G, De Benedetti F. Macrophage activation syndrome: different mechanisms leading to a one clinical syndrome. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):5. doi:10.1186/s12969-016-0130-4 15. De Benedetti F, Prencipe G, Bracaglia C, Marasco E, Grom AA. Targeting interferon-γ in hyperinflammation: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(11):678-691. doi:10.1038/s41584-021-00694-z 16. Grom AA, Horne A, De Benedetti F. Macrophage activation syndrome in the era of biologic therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(5):259-268. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2015.179 17. Russell SE, Moore AC, Fallon PG, Walsh PT. Soluble IL-2Rα (sCD25) exacerbates autoimmunity and enhances the development of Th17 responses in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47748. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047748 18. Schulert GS, Grom AA. Macrophage activation syndrome and cytokine-directed therapies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(2):277-292. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2014.03.002 19. Crayne C, Cron RQ. Pediatric macrophage activation syndrome, recognizing the tip of the iceberg. Eur J Rheumatol. 2020;7(Suppl1):S13-S20. doi:10.5152/eurjrheum.2019.19150 20. Ng S, Talbot J, Clinch J, Ohlsson V, Rogers V. O15 Recognition of subclinical macrophage activation syndrome in an adolescent systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis patient receiving tocilizumab: a case report. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2020;4(Suppl 1):rkaa054.003. doi:10.1093/rap/rkaa054.003